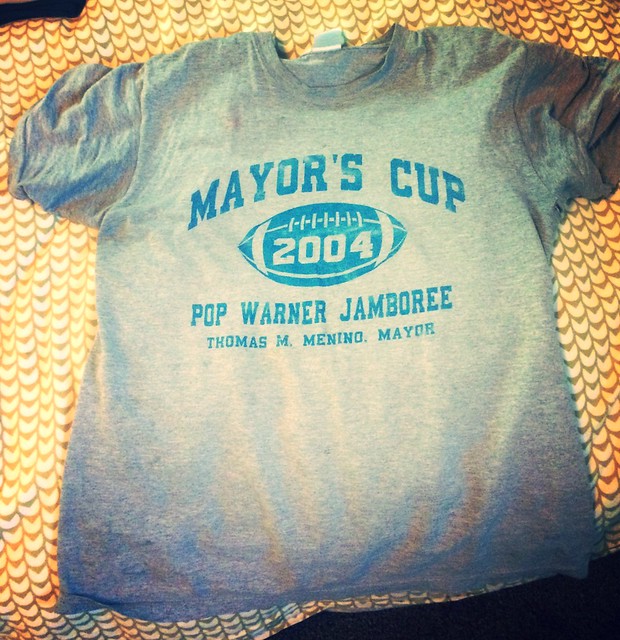

The most expensive T-shirt I own

/ I didn't buy this t-shirt nor did it come with a price tag affixed. But I know that it's the most expensive piece of clothing I own.

I didn't buy this t-shirt nor did it come with a price tag affixed. But I know that it's the most expensive piece of clothing I own.

I don't treat it as such. I don't handle it gingerly, afraid that it might tear at the seams or unravel at the edges. I don't wash it irregularly so that its painted letters don't quickly fade. In fact, I wear it often and with pride because, as I mentioned, it is the most valuable piece of clothing I own.

When I was a youth worker for the City of Boston, I served every day at a community center in a neighborhood I had never been to before, not even driven through once. I didn't know anyone who lived there, in the patchwork of tidy triple-deckers and eateries that ranged from Salvadorean pupusa shops to Italian eateries to Chinese restaurants to Vietnamese pho houses. The neighborhood comprised effectively an island and most of the kids who grew up there knew one another. They confessed they didn't bother skipping school because someone would see them on the corner and call their mother.

Most of the youth I worked with lived in a housing development complex. I had never visited a housing development, never walked through the block after block of unimaginatively designed structures and marveled at how there was no green space, how there were so many children living throughout the complex and yet there was no space for them to play that was not concrete.

So the kids came to the community center where I was based, where I did a job for which I received no training, in a place I wasn't so much as even acquainted with, with a population of kids whose lives were unfathomably different than anything I had known. In my arrogance, I thought that I was the good thing that had come their way. A college graduate, a creative program person, a self-proclaimed lover of kids.

I did everything wrong. I presumed when I should have asked. I got angry when I should have laughed. I muscled through on my own when I should have sought help. Most of the programs I ran were a bust. The boys humored me, the girls came and asked me questions about sex. I thought I had what they needed, if I could just organize a better program of activities. If only they would come every day, I could meet their needs. My bosslady was so patient with me. She would say, "The only problem with you is that yaw not from heeyah." I laughed and only sort of knew what she meant. I started asking a music shop if they would let me take their leftover sample CDs to give away as prizes. The kids started looking at me like a prize dispenser, popping them out like Pez. I made $22,000 a year before taxes. I still thought it was about me.

During an outdoor program I organized, there were a ton of water balloons which, since these were teenagers, became a ton of water buckets filled and thrown. I didn't have a change of clothes. Someone handed me this Mayor's Cup t-shirt, one from a stack that were just hanging around in the closet.

By the time I was a year into the job, I knew that I would be getting married, that I would be moving on. I took the LSAT with my co-worker Kamau. We knew we couldn't stay making the money we were making. We wanted to do the most good.

After I got back from my honeymoon, I started interviewing for other jobs. I had deferred law school but I still wanted get home earlier in the day to spend time with my hew husband. I soon found 9-5 administrative job that I could walk to from our apartment.

On my last day working at the community center, I had not wanted to make a big deal about my departure. I wasn't sad that I was leaving, but I was sad that I wouldn't see how the kids would grow. I wouldn't know who went to college and who had a growth spurt over the summer. I wouldn't hear their voices change and watch their girlfriends change and offer to drive them home when they didn't have enough change for the bus fare.

On my last day, only one kid came back to say good-bye. He had been by far one of the hardest kids to reach. He hated school and just wanted to play basketball. He seemed to break one girl's heart on Monday and have found a new one to break by Tuesday. I didn't understand his goals; I didn't understand how I could help him.

But he came back to say good-bye. He sat with me in the office, his pristine baseball hat with the manufacturer's silver sticker still on the underside of the wide brim. He looked up from under that wide brim and asked me about my plans. I told him I thought I'd probably go back to school so that I could eventually teach. He nodded and bounced a basketball under the table. We hugged it out and he went to go shoot hoops.

Whenever I wear my Mayor's Cup t-shirt, I think of what it represents. I think how it was handed to me when I had nothing else to wear because I was a pilgrim. I remember how hard it was to earn respect as a pilgrim. I think how I'd never had to learn how to love kids who were hard to love before. I remember how after nearly two years, they returned that love to me. At least one did. He handed it to me like it was a free t-shirt. One that I would be so grateful to receive, one that still makes me feel so privileged and proud, not only because I got to love but was loved well in the end.